The following six suggestions and graphic (left) come from Hadaf Hayomi (a regular newsletter on the Talmud), explaining the possible options and which I think is the best summary I have seen. No point in re-inventing the wheel, but I have added a few of my own thoughts in brackets:

The broken vav- vav k'tia

Throughout the halachah

it is stressed that letters must be written as a complete guf

(body) except the kuf

and heh

which do have breaks (though didn't used to in the past). Also if letters are faded or partly illegible then the work is pasul

(invalid).

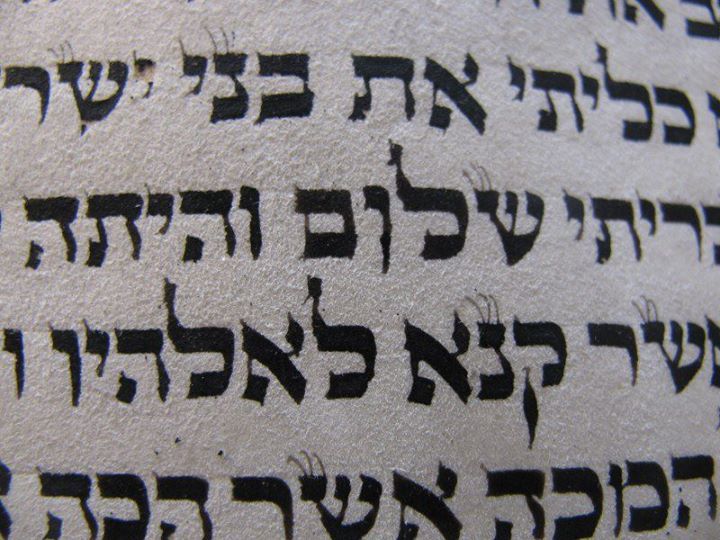

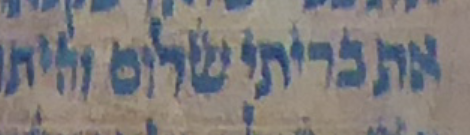

However there is one exception were the scribe is mandated to make the letter incomplete. The letter in question in the vav in the word shalom in Numbers 25:12. This must be written with a break in the vertical line according to the Ritva (R. Yom Tov ben Avraham Ishbili Spain c. 1250-1330), though some think it either a small vav or a normal vav but a little shorter "in front". In fact there are quite a few opinions and Yemenite Sifrey Torah do not preserve this tradition at all.

However there is one exception were the scribe is mandated to make the letter incomplete. The letter in question in the vav in the word shalom in Numbers 25:12. This must be written with a break in the vertical line according to the Ritva (R. Yom Tov ben Avraham Ishbili Spain c. 1250-1330), though some think it either a small vav or a normal vav but a little shorter "in front". In fact there are quite a few opinions and Yemenite Sifrey Torah do not preserve this tradition at all.

1. It is a small vav

(though this is not mentioned as one of the small letters and would be referred to as z’ira

(small) and not k’tia)

2. The leg of the vav is shorter (though this in part would look a bit like a yud without the curve to the leg, so may be declared pasul because of that)

3. First a yud is written (though without the curve) and the a space is left and then line is added to complete the vav.

4. A regular vav is written and then a crack is made in the leg by scraping out the ink and (this would divide it into two and I don't think this is acceptable because of chok tochot - carving out to form a letter - even though it technically is invalidating a normal vav form)

5. The same again, but this time the crack is a diagonal nick which doesn’t quite break the letter into two (I have same problem here as it rather suggests chok tochot, as this particular letter form would be formed by scraping and not writing).

6. A vav with a slightly short leg is written then a small line is added to complete the length.

It would seem to me that 3 or 6 would be the most suitable and certainly that's what I've tended to see the most of.

2. The leg of the vav is shorter (though this in part would look a bit like a yud without the curve to the leg, so may be declared pasul because of that)

3. First a yud is written (though without the curve) and the a space is left and then line is added to complete the vav.

4. A regular vav is written and then a crack is made in the leg by scraping out the ink and (this would divide it into two and I don't think this is acceptable because of chok tochot - carving out to form a letter - even though it technically is invalidating a normal vav form)

5. The same again, but this time the crack is a diagonal nick which doesn’t quite break the letter into two (I have same problem here as it rather suggests chok tochot, as this particular letter form would be formed by scraping and not writing).

6. A vav with a slightly short leg is written then a small line is added to complete the length.

It would seem to me that 3 or 6 would be the most suitable and certainly that's what I've tended to see the most of.

One of my funniest moments as a scribe came when a Rabbi called me up and said they had a found a letter with a break in it and could I come in and repair it. It was only one letter so it wouldn't take long.

"It isn't in parshat Pinchas in the word shalom in a vav?" I asked innocently.

"Yes" said the Rabbi somewhat surprised, was I perhaps telepathic or otherwise possessing some kind of super human powers, "how did you know that?"

"It's supposed to be there. It's a special visual midrash."

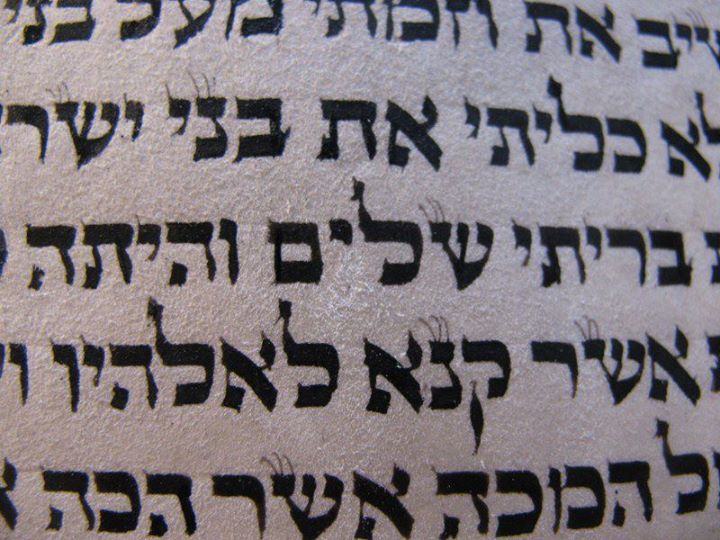

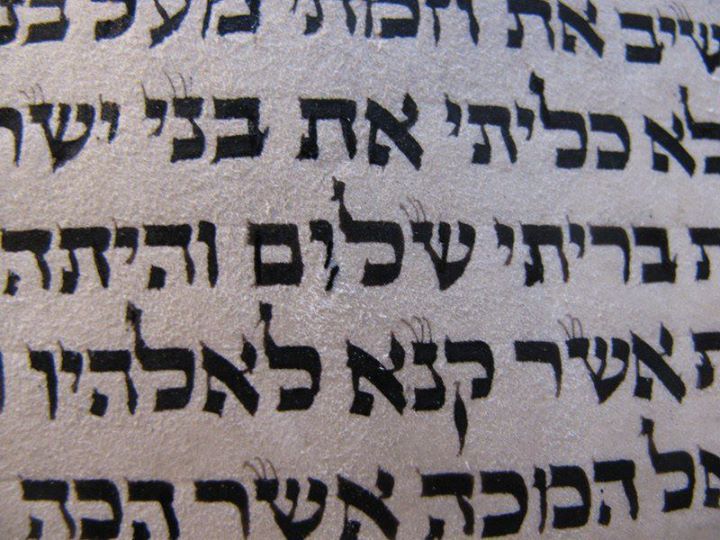

Interestingly the reverse appeared in a Torah from Wimbledon I repaired. Having reached parshat Pinchas - which is always in the worst condition as it is the most used - I noticed that someone may well have got there before me; as I think someone 'repaired' the vav k'tia (see below) as there was a little blob of ink on where the break should have been. You can see the correction sequence below in the image carousel.

"It isn't in parshat Pinchas in the word shalom in a vav?" I asked innocently.

"Yes" said the Rabbi somewhat surprised, was I perhaps telepathic or otherwise possessing some kind of super human powers, "how did you know that?"

"It's supposed to be there. It's a special visual midrash."

Interestingly the reverse appeared in a Torah from Wimbledon I repaired. Having reached parshat Pinchas - which is always in the worst condition as it is the most used - I noticed that someone may well have got there before me; as I think someone 'repaired' the vav k'tia (see below) as there was a little blob of ink on where the break should have been. You can see the correction sequence below in the image carousel.

Photos above and below © Mordechai Pinchas.

Finally, as I mentioned the Yemenites do not preserve this tradition and in their Sifrey Torah

the vav

is always complete as you can see from the photo I took in a Yemenite

synagogue in Re'ut.

Mordechai Pinchas