- Home

- Activities

- Letters

- Diary

- Tools

- Books

- Education

- Sources

- Oddities

-

MORE

- About me

- Sefer Torah

- Tefillin

- Pittum HaKtoret

- Ketubah

- Alefbet

- Diary 1

- Diary 2

- Diary 3

- Diary 3a

- Diary 4

- Diary 5

- Diary 6

- Diary 7

- Diary 8

- Repairs

- More Repairs

- Yet More Repairs

- Diary 45

- Diary 39

- Broken Vav

- Joined Kuf

- Diary 11

- Diary 46

- Diary 47

- Siyyum

- Some siyyumim

- Diary 26

- Diary 27

- Raised vav

- Kulmus

- Giddin

- Purim shpiels

- Diary 40

- Diary 42

- Kulmus Books

- Mezuzah

- Large letters

- Diary 48

- Diary 49

- Diary 18

- Sefer Binsoa

- Dyo

- Klaf

- In the End

- Adventures in Practical Halachah

- Sefer Tagin Fragments from the Cairo Genizah

- Diary 50

- Megillat Esther

- My first megillah

- 2018 Megillah

- The E-Fuzzy

- Ketubah 2 Avielah's Gallery

- Publications and audio visual

- Old Harrys Ketubah

- Commemorative illuminations

- Diary 51

- Diary 52

Diary 5

Diary 5 - Dozens of rules and that’s just one letter!

The m'zuzah

was almost complete. I had completed the holy names of God with the appropriate degree of kavannah

and I scanned it into the computer and sent a copy to Vivian for checking.

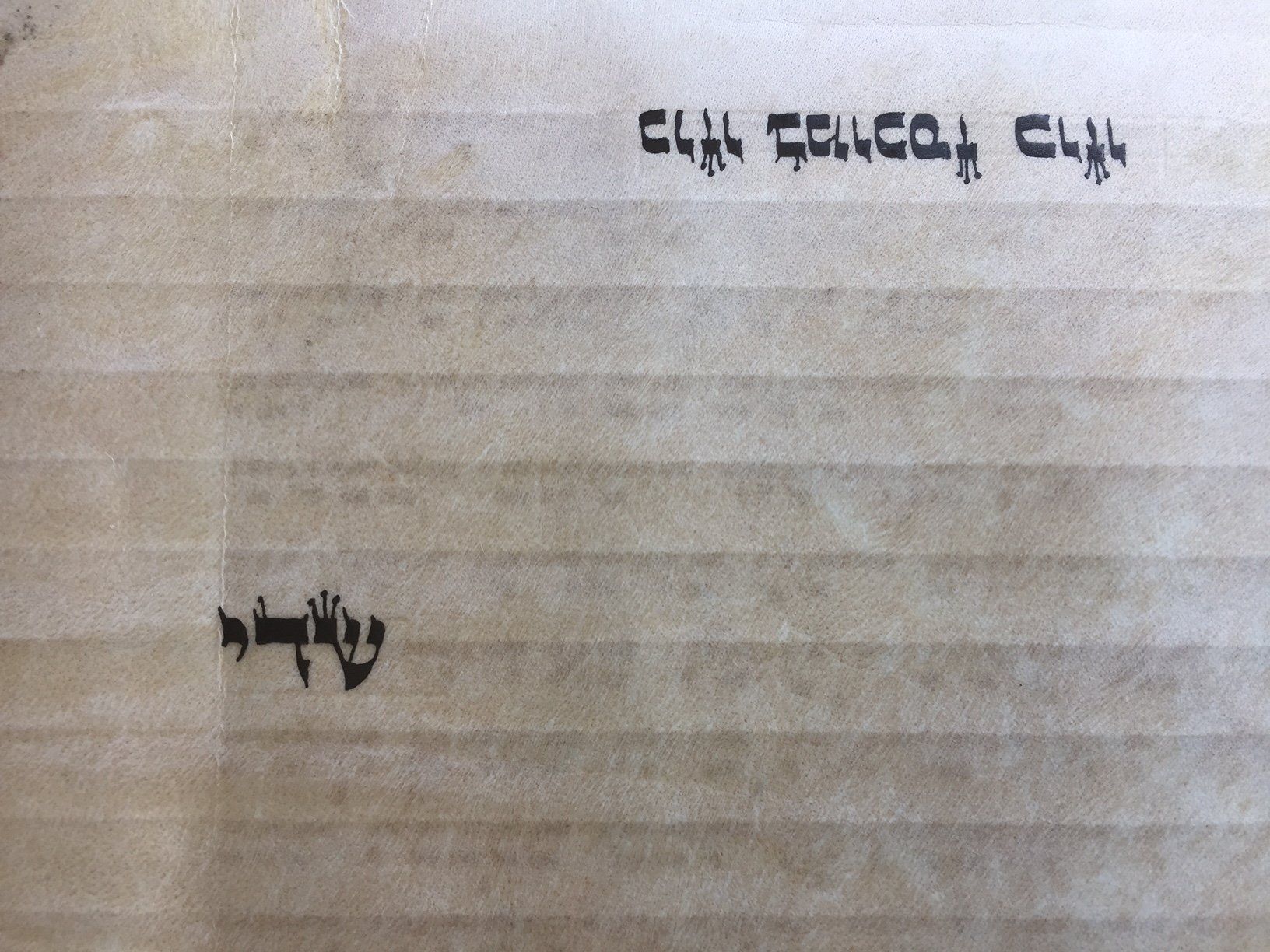

There was a mistake! A small mistake true, but nonetheless a mistake. In the very last word of the 6th line I was missing a letter yud. Whilst I corrected it at the time, as I learnt studying the halachah my m'zuzah was not actually correctable as the letters must be written k’sidran (in their order) and thus it was pasul (invalid). However it is noted by the Va’ad Mishmeret S"TAM that many less than meticulous sofrim do allow correction, but this means their work is invalid. My first m'zuzah was merely for practice and 'show and tell' and never to be used, so this isn’t a problem, but I have been even more careful since. Even then the m'zuzah was not finished as on the reverse were needed two additional elements. The word Shaddai - another name of God) for which there are a number of explanations the most popular (but least likely) explaining it as an acronym shomer d’latot yisrael - the guardian of the doors of Israel - and the even more peculiar phrase kuzo b’mochsez kuzo which is written upside down directly behind the words hashem elokeynu hashem and which are the next letters on in the alphabet. Don’t believe me - check your m'zuzot - which you should do at least every 3.5 years anyway!

Why? The usual explanation is that it’s kabbalah (mysticism) but Vivian and I weren’t satisfied with that and we searched for some real hard facts - that we never really found.

There was a mistake! A small mistake true, but nonetheless a mistake. In the very last word of the 6th line I was missing a letter yud. Whilst I corrected it at the time, as I learnt studying the halachah my m'zuzah was not actually correctable as the letters must be written k’sidran (in their order) and thus it was pasul (invalid). However it is noted by the Va’ad Mishmeret S"TAM that many less than meticulous sofrim do allow correction, but this means their work is invalid. My first m'zuzah was merely for practice and 'show and tell' and never to be used, so this isn’t a problem, but I have been even more careful since. Even then the m'zuzah was not finished as on the reverse were needed two additional elements. The word Shaddai - another name of God) for which there are a number of explanations the most popular (but least likely) explaining it as an acronym shomer d’latot yisrael - the guardian of the doors of Israel - and the even more peculiar phrase kuzo b’mochsez kuzo which is written upside down directly behind the words hashem elokeynu hashem and which are the next letters on in the alphabet. Don’t believe me - check your m'zuzot - which you should do at least every 3.5 years anyway!

Why? The usual explanation is that it’s kabbalah (mysticism) but Vivian and I weren’t satisfied with that and we searched for some real hard facts - that we never really found.

Above: The reverse of a

m'zuzah sporting some additional elements. You can just make out the impressions of letters showing through from the otehr side. In older times, some scribes used to add names of angels and other biblical verses and Rambam got very upset about this. There are some great pictures of these in

Otser Hilchot M'zuzah. Photo © Mordechai Pinchas.

So far, I’ve spent a lot of time talking about the actual ‘doing’ of sofrut. Just as important, if not more so, is the study associated with all the intricate laws governing the letter forms, the rituals, the parchment, the ink etc.

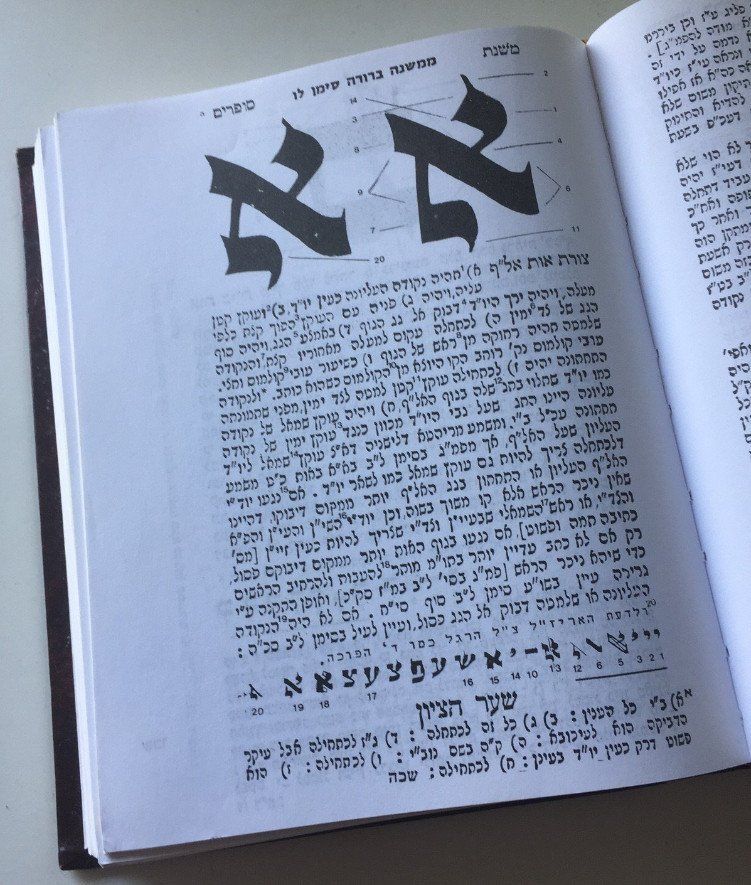

This is not that simple as the laws are not all gathered in one place. Many collections of laws purport to be comprehensive, I discovered numerous versions of halachik digests. The big downer was that since this is a very specialist area very few of them have been translated from the original Hebrew, so it was jolly hard work, but quite and interesting challenge!

So far, I’ve spent a lot of time talking about the actual ‘doing’ of sofrut. Just as important, if not more so, is the study associated with all the intricate laws governing the letter forms, the rituals, the parchment, the ink etc.

This is not that simple as the laws are not all gathered in one place. Many collections of laws purport to be comprehensive, I discovered numerous versions of halachik digests. The big downer was that since this is a very specialist area very few of them have been translated from the original Hebrew, so it was jolly hard work, but quite and interesting challenge!

Below: A page fromMishnat Sofrim showing the rules governing the writing of the letteraleph. Photo © Mordechai Pinchas.

Being a sofer is just as much about understanding and adhering to the strict rules as much as the writing and whilst this element of my learning isn’t quite as eventful (or as funny) as some of the other things I have described in my preceding articles, it is crucial. Assisting in my learning, believe it or not is the world wide web. Aside from advertising their services on the internet, a number of scribes in Israel and America have set up very educational sites (in English!) with lots of detail, examples of work and in some cases summaries or translations of specific laws.

One might think that learning a 3,000 year-old trade that is wedded to the natural and is about as old-fashioned in communication terms as you can get - being one step up from cuneiform - wouldn’t be compatible with the high-tech computer world. You’d be wrong. One site even boasts that as well as the prescribed checks by three rabbis for accuracy in a Sefer Torah they offer an additional validation by computerised scanning. Most importantly I learnt from the web that most apprentice scribes start with Megillat Esther, for the simple reason that it is the one piece of scribal work that does not mention the holy name of God. Was this the start of something big? Find out next time.

Mordechai Pinchas

Being a sofer is just as much about understanding and adhering to the strict rules as much as the writing and whilst this element of my learning isn’t quite as eventful (or as funny) as some of the other things I have described in my preceding articles, it is crucial. Assisting in my learning, believe it or not is the world wide web. Aside from advertising their services on the internet, a number of scribes in Israel and America have set up very educational sites (in English!) with lots of detail, examples of work and in some cases summaries or translations of specific laws.

One might think that learning a 3,000 year-old trade that is wedded to the natural and is about as old-fashioned in communication terms as you can get - being one step up from cuneiform - wouldn’t be compatible with the high-tech computer world. You’d be wrong. One site even boasts that as well as the prescribed checks by three rabbis for accuracy in a Sefer Torah they offer an additional validation by computerised scanning. Most importantly I learnt from the web that most apprentice scribes start with Megillat Esther, for the simple reason that it is the one piece of scribal work that does not mention the holy name of God. Was this the start of something big? Find out next time.

Mordechai Pinchas